In a previous article in this series, we mentioned an odd comment that God made when He gave Abraham a glimpse of the future:

As for yourself, you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a good old age. And they shall come back here in the fourth generation, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.“

Genesis 15:7-16 (ESV), emphasis added

The obvious questions that come to mind: Who were the Amorites, and why was the timing of the Exodus linked to their iniquity? What was their iniquity? What could they have done that was so bad that God made it a signpost on the road to Revelation? Whatever it was, the evil of the Amorites was legendary among the Jews:

And the Lord said by his servants the prophets,

“Because Manasseh king of Judah has committed these abominations and has done things more evil than all that the Amorites did, who were before him, and has made Judah also to sin with his idols, therefore thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Behold, I am bringing upon Jerusalem and Judah such disaster that the ears of everyone who hears of it will tingle.

2 Kings 21:10-12 (ESV), emphasis added

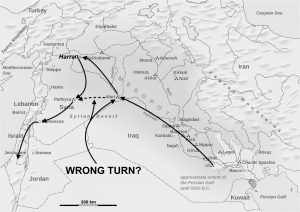

Manasseh was king of Judah about seven hundred years after the Exodus, nearly 1,200 years after Abraham was first called from Ura, near Harran in northern Mesopotamia (not Ur in Sumer–I addressed that in an earlier article). Whatever the Amorites did, it was bad.

The Amorites were incredibly resilient. They hung around, and dominated for a long time, a part of the world where people have been fighting each other since the time of Nimrod. They were a Semitic speaking people who occupied nearly the entire Near East during the first half of the 2nd millennium BC. According to the Bible, the Amorites descend from Noah’s son, Ham, by way of Canaan. However, even though Ham is considered the progenitor of various African races, Egyptian artists usually represented Amorites with fair skin, light hair, and blue eyes.

The Amorites were first mentioned in Mesopotamian records around 2400 BC, just before Sargon the Great turned Akkad from a city-state into an empire. They were known to the city-dwelling Sumerians as the MAR.TU, who considered them savage, uncouth, and generally unpleasant.

The MAR.TU who know no grain… The MAR.TU who know no house nor town, the boors of the mountains… The MAR.TU who digs up truffles… who does not bend his knees (to cultivate the land), who eats raw meat, who has no house during his lifetime, who is not buried after death[.]1

Scholars haven’t reached a consensus over just where the Amorites came from. The Ebla texts refer to an Amorite LU.GAL, or king, named Amuti, in the 2300s BC. The Amorite kingdom, MAR.TUki in Sumerian, seems to have been centered in Syria around Jebel Bishri, a mountain on the west bank of the Euphrates about 30 miles west of Deir ez-Zor. The mountain of the Amorites, called Bašar back in the day, was the site of a military victory led by the Akkadian king Narām-Sîn, grandson of Sargon the Great, over a coalition of Amorites led by Rish-Adad, the lord of a small city called Apishal.

Evidence uncovered by a team of Finnish researchers who began work at Jebel Bishri in 2000 indicates that the main urban center of MAR.TUki in the third millennium BC was Tuttul, a city on the Euphrates near the modern city of Raqqa. Tuttul was settled by the 26th century BC and was sacred to Dagan, chief god of the local pantheon. A second temple of Dagan was built later at Terqa, south of Tuttul on the Euphrates about halfway to Mari, which was near where the Euphrates crosses from Syria into Iraq.

This leads to a bigger question: What exactly was the religion of the Amorites? Might that shed some light on why Yahweh called them out when He made the covenant with Abraham?

Judging by personal names in the earliest records, it looks as though there were originally only two main gods of the Amorites—the moon-god, Ereah or Yarikh (from which Jericho, a center of moon-god worship, got its name), and “the” god, El.

That should interest anyone who’s read any of the Old Testament. Besides being the name of the chief god of the Canaanite pantheon, El was one of the names the prophets applied to Yahweh. Remember that El was the only name by which Yahweh was known to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. That’s significant because they lived during the time the Amorites controlled the Near East.

Meanwhile, the moon-god, while not as well-known as Satan, Baal, or Marduk, enjoyed a long run as one of the most influential gods of the Near East. After the defeat at Jericho, Yarikh, called Sîn (pronounced “seen”) by the Akkadians and Nanna by the Sumerians, reemerged as the chief god of Babylon nearly a thousand years later under its last king, Nabonidus (reigned 556–539 BC). And you can make a strong case that the moon-god today leads what may become the largest religion on the planet within the next half-century.

However, as they gained political control over regions previously governed by the Akkadians and Sumerians after 2000 BC, the Amorites began adopting the gods of their subjects. A classic example is the Amorite chief, Šamši-Adad I. His father, Ila-kabkabu (possibly “El is my star”), had been the king of Terqa. After being forced to flee to Babylon during the reign of Narām-Sîn of Akkad, Šamši-Adad eventually returned home, overthrew Narām-Sîn’s successor, and became the first Amorite king of Assyria.

Šamši-Adad, whose name includes that of the storm-god of Aleppo, named the son he placed on the throne of Mari, whose territory bordered on Yamḥad (Aleppo), Yasmah-Adad. The son who governed the Akkadian part of his realm was named Išme-Dagan. Both names mean “(deity) hears,” but presumably Adad and Dagan were more acceptable to the subjects of their respective parts of the realm than Amorite gods like Ilu (El) or Ereah (Yarikh).

The Amorites, like the later Israelites, were subdivided into tribes. By the time of Abraham, the Amorites were divided into two main groups—the Binū Yamina (“sons of the right hand,” or “southerners”) and the Binū Sim’al (“sons of the left hand,” or “northerners”). The division seems based on an ancient agreement over pasturing rights: The Bensimalites took their herds to the Khabur River triangle in what is today northern Syria, while the Benjaminites pastured their flocks in the territories of Yamḥad (Aleppo), Qatna, near modern-day Homs, and Amurru, the mountains of northern Lebanon to the southeast of Ugarit.

Sometime around the end of the third millennium BC, the Sumerian dynasty of Ur collapsed under the weight of intrusions by Amorite tribes and invasions from Elam. The century beginning about 2000 BC is hazy, a period of history that we’ll probably never decipher. When the fog lifted around 1900 BC, Amorites ruled nearly all the power centers in Mesopotamia and the Levant. They’d spread out from their traditional base on the steppes of northern Syria and Iraq to as far as the Jordan River in the southwest, southern Turkey in the north, and as far southeast as an insignificant village on the Euphrates that would soon play a major role in world history—some of which hasn’t happened yet.

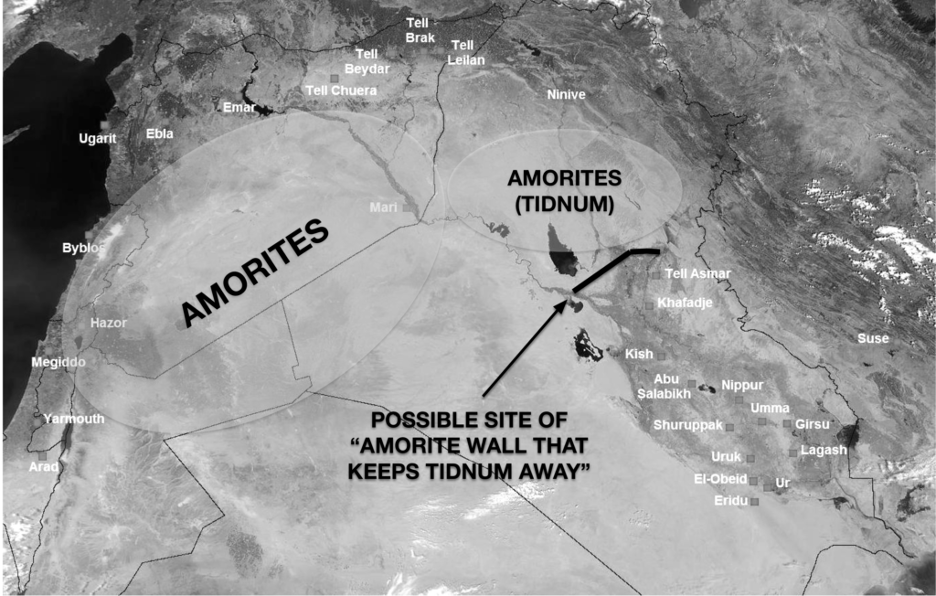

Because of their association with Jebel Bishri and the steppes of Syria, west of Sumer, the Sumerian word for Amorite, MAR.TU, became a synonym for the compass point west, just like the Hebrew link between Mount Zaphon and tsaphon, the compass point north. However, there was another area occupied by Amorites. Northeast of modern Baghdad, around the Diyala River valley, an Amorite tribe called the Tidnim, Tidnum, or Tidanum was a major source of trouble for the Sumerians at least as far back as 2800 BC, when the first mention of a “chief” or “overseer” of the tribe is found at Ur. (However, one of the peaks of Jebel Bishri was called Jebel Diddi, or Mount Diddi, which may come from Didānum—same name, different transliteration—so the tribe may have history there as well.)2

The Tidnum of northeast Mesopotamia were so troublesome that the last Sumerian kings of Ur built a wall, possibly 175 miles long, from the Euphrates across the Tigris to a site along the Diyala. The project was called the bad mar-du murīq-tidnim, or, “Amorite wall which keeps the Tidnum at bay.”

It may have been more of a border fence than a Great Wall of China-type structure. The only mentions of the wall are the names of the fourth and fifth years of king Šu-sin’s reign, and that there are no mentions of it at all among the piles of tablets that recorded the king’s business in Ur.

However, what Šu-sin’s building project did was firmly establish the link between the Amorites and the Tidanum. And that’s important. We’ll explain why next week.

1 Chiera, Edward & Kramer, Samuel Noah & University of Pennsylvania. University Museum. Babylonian Section. (1934). Sumerian Epics and Myths, Chicago, Ill : The University of Chicago Press, Plate nos. 58 and 112.

2 Bodi, Daniel. “Is There a Connection Between the Amorites and the Arameans?”, Aram 26:1 & 2 (2014), p. 385.