Babylon was founded by an Amorite chief named Sumu-Abum of the Amnanum tribe, who got the party started around 1894 BC by grabbing land from a neighboring town, Kazallu. Babylon was so unimportant that the first four kings of the dynasty didn’t even call themselves “king of Babylon.” It wasn’t until Hammurabi put it on the map in the eighteenth century BC that the city became Babylon as we think of it. Beginning around 1792 BC, he conquered all of Sumer, Akkad, and the Euphrates Valley as far as Mari, where Hammurabi not only defeated his “old friend” and “brother,” the Amorite king Zimri-Lim, but he apparently ordered the ritual destruction of the palace and main temple there.[1]

That points us back toward the theme of the book, which is identifying the spirits behind geopolitics—“theopolitics,” to borrow a phrase coined by my wife, Sharon.

Scholars typically define the name of Babylon’s greatest king as meaning “my kinsman is a healer,” from the Amorite term ʻAmmurāpi, derived from ʻAmmu (“paternal kinsman”) and Rāpi (“healer”). But rāpi is from the same root as the biblical word “Rephaim.” There isn’t a single example in Canaanite texts where the rapha are healers. It’s more likely his name means “my kinsmen are Rapha,” or more simply, “my fathers are the Rephaim.”[2]

A genealogy of the dynasty of Hammurabi, compiled about a hundred years after he died, names one of the ancestors of the Amorite kings of Babylon as Ditanu,[3] which, you’ve noticed, is the name of the ancient Amorite tribe that, as we showed in an earlier article, gave its name to the old gods of the Greeks, the Titans. That same Ditanu was claimed as an ancestor by the ruling houses of at least two other powerful Amorite kingdoms between the eighteenth and thirteenth centuries BC. Ditanu was one of “seventeen kings who lived in tents” named as ancestors of Shamshi-Adad, an Amorite king who ruled northern Mesopotamia around the time of Hammurabi.[4]

About five hundred years later, the Amorite kingdom of Ugarit summoned a group called “the council of the Ditanu” from the netherworld during necromancy rituals,[5] and a temple to the Ditanu confirms that they were believed to be among the gods.[6]

The kingdom established by the Amorite dynasty that produced Hammurabi has cast a long shadow across history. It built on earlier religious and cultural traditions established by the Sumerians and Akkadians, but God called out Babylon and the Amorites specifically for their wickedness. The occult religious system of Babylon was so vile it became a symbol of evil from the time of Moses through the end of the apostolic age. John the Revelator used Babylon to represent the corrupt end-times church of the Antichrist.

Of course, the kingdom of Hammurabi’s Babylon was doomed to collapse almost as soon as he established it. After the great lawgiver’s death around 1750 BC, his successors kept the kingdom intact for a while, but Elamites from the east, Assyrians from the north, and people in the far south broke away, so that by about 1600 BC, the Amorite dynasty in Babylon once again controlled only the land around the city. Still, the power of Hammurabi was such that southern Mesopotamia has been called Babylonia ever since the time of Abraham.

In 1595 BC, an army from the new Hittite kingdom in central Anatolia (modern Turkey), led by king Ḫattušili I, conducted a long raid down the Euphrates. Bypassing the Assyrians in northern Mesopotamia, the Hittites sacked Mari and then ejected the Amorites from Babylon. The Hittite withdrawal back into Anatolia left a vacuum that was filled about twenty-five years later by the Kassites, a mountain people from western Iran who captured Babylon and controlled it and much of the territory once ruled by Hammurabi for the next four hundred years.

This makes the Kassites, not the Amorites or Chaldeans, the people who ruled Babylonia the longest, and the Kassite kingdom endured from the time of Jacob until the period of the judges in Israel.

Meanwhile, Amorites slowly assumed power in northern Egypt. During the time of the Hebrew sojourn, the rulers of Egypt—at least the part where the Israelites settled, the Nile delta—were Amorites. They were called “Hyksos” by native Egyptians, a word that roughly translates as “rulers of foreign lands.” Egyptologists refer to it as the Second Intermediate Period, which lasted from about 1750 BC to 1550 BC. It appears that after a series of weak rulers, Egypt was divided between a native kingdom in the south based at Thebes and the foreign Hyksos in Lower (northern) Egypt, whose capital city was Avaris in the northeastern Nile delta. The Hyksos brought with them their art, their architecture, their weapons, and their gods.

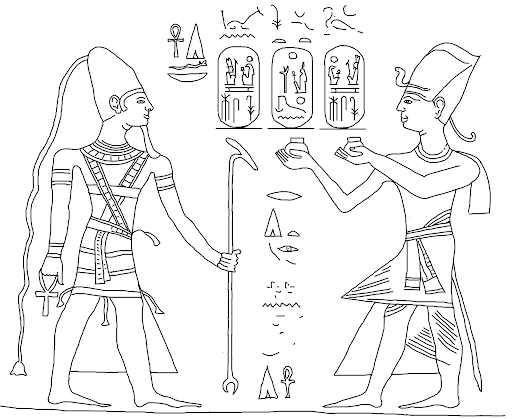

This helps make sense out of the greatest miracle that God performed during the Exodus. You see, even though the Hyksos were run out of Egypt by the Egyptians about a hundred years before Moses led Israel to Mount Sinai, the chief god of the Hyksos, Baal, was worshiped in Egypt for several centuries more. Ramesses the Great, who ruled Egypt about two hundred years after the Exodus, was a Baal worshiper. He set up a stela at Pi-ramesses, near the site of the abandoned Hyksos capital Avaris. The engraved memorial stone commemorated Set’s four hundredth anniversary of ruling at Tanis,[7] but the god was depicted exactly like the images of Baal found in Syria, with a tasseled Canaanite kilt and conical headdress with a streamer. The gods of the Amorites influenced Egypt far more than we’ve been taught; the Amorite Hyksos and the Egyptian pharaohs who came after them worshiped Baal-Set as a single entity.[8]

That’s the key to understanding the parting of the Red Sea: In Canaanite religion, Baal became king of the gods by fighting and beating the sea-god, Yamm. Amorite, Canaanite, and Phoenician sailors worshiped Baal as their patron and protector for more than a thousand years.

So, the parting of the Red Sea, which happened right in front of a place called Baal-zephon, named for Mount Zaphon, which the Amorites believed was the home of Baal’s palace, demonstrated Yahweh’s mastery over the chief god of Israel’s oppressors.

Have you ever noticed that God told Moses to turn the Israelites around and camp in front of Baal-zephon to wait for the Egyptian cavalry to catch up?[9] God didn’t just deliver Israel from the hand of Pharaoh; He delivered Israel from the hand of Baal!

In short, the social and religious culture of the Amorites was the world from which God called the patriarchs and prophets to establish His chosen people in the land where His Name would dwell, Canaan.[10] The language, customs, and, most of all, the gods of the Amorites dominated the world of the ancient Hebrews.

The Amorites faded from history after the conquest of Canaan, at least under the name “Amorite.” But their descendants continued to play important roles in ancient Israel. The Arameans, whom scholars generally agree were descended from the Amorites,[11] set up kingdoms in Damascus and elsewhere in Syria after the so-called Bronze Age collapse, a period of violence and chaos in the eastern Mediterranean around 1200 BC. They were a thorn in the side of Israel (and Judah, after Solomon’s death) for hundreds of years. The Chaldeans, who established the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the seventh century BC, likely emerged from nomadic Amorite tribes who migrated from the west into southeastern Mesopotamia sometime around 900 BC.[12]

The greatest Chaldean king, Nebuchadnezzar, is generally who comes to mind when we think of Babylon, but that city was around for a long, long time before the Chaldeans took it over. Think about the time scale—Hammurabi the Great died more than eleven hundred years before Nebuchadnezzar was born.

Now, who was the king of England in 923 AD?[13]

Exactly. Eleven hundred years is a very long time. Yet the gods of Mesopotamia were the same, with few exceptions.

Meanwhile, the Phoenicians, descendants of the Amorites who occupied the Mediterranean coast of Syria and Lebanon, brought their culture and religion into Israel from the time of the judges to the time of Jesus and beyond. For example, Jezebel, the infamous wife of Israel’s king Ahab, was from Tyre, which competed with the Greeks and Romans for control of trade on the Mediterranean for centuries. Carthage, a colony in north Africa established by Tyre around the time of Jehoash, king of Judah (circa 814 BC), nearly destroyed Rome in the late third century BC. Temples to Phoenician gods like Melqart, Baal-Hammon, and Tanit have been found as far away as Spain.

And tophets, ritual places of burial for infants and children sacrificed to Baal-Hammon, similar to the Tophet near Jerusalem where children were burned as offerings to Molech, have been excavated at Carthage and multiple sites on Sicily and Sardinia.

Here’s the point of this brief history: The iniquity of the Amorites still affects the world today. And the gods behind it are pushing the world toward Armageddon.

[1] Sara Tricoli, “The Ritual Destruction of the Palace of Mari by Hammurapi under the Light of the Cult of the Ancestors’ Seat in Mesopotamian Houses and Palaces.” In Krieg und Frieden im Alten Vorderasien (Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2014), 795-836.

[2] Schmidt, op. cit., 158–159. Also Derek P. Gilbert, Last Clash of the Titans (Crane, Mo.: Defender, 2018), 84.

[3] Nicolas Wyatt, “À la Recherche des Rephaïm Perdus.” In The Archaeology of Myth, ed. Nicolas Wyatt (London: Equinox, 2010), 595.

[4] Ibid.

[5] KTU 1.161, which was apparently a ritual performed at the coronation of the last king of Ugarit, Ammurapi III. Note that he shared the same name as his more famous predecessor, Hammurabi of Babylon, who lived more than five hundred years earlier.

[6] Jordi Vidal, “The Origins of the Last Ugaritic Dynasty.” In Altorientalishce Forschungen 33 (2006), 169.

[7] James B. Pritchard (ed.), Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 253.

[8] Niv Allon, “Seth is Baal: Evidence from the Egyptian Script.” In Egypt and the Levant, Manfred Bietak (ed.) (Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2007), 15–21.

[9] Exodus 14:1–2.

[10] Deuteronomy 12:11.

[11] Bodi, op. cit., 383–409.

[12] Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq. London: Penguin Books, 1992, 281.

[13] Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, in case you’re wondering.